The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is a complex hinge joint that permits the mandible to smoothly glide forward while opening the mouth. Temporomandibular Disease/Disorder/Dysfunction (TMD), often misreferred to as simply "TMJ," is a complex condition involving abnormalities in the TMJ(s) or related areas. TMD is often categorized into two primary groups, "intra-articular" (within the TMJ) and "extra-articular" (outside the TMJ). In cases where surgery is either necessitated or desired, the subcategories of these two diagnostic groups would help determine surgical prognosis. Common diagnoses that may mandate surgical intervention include, but are not limited to, internal derangement, ankylosis, and bone disease. Bear in mind surgery is a massive, complex, and heavily debated domain where we cannot cover all existing procedures comprehensively, while sustaining integrous information. Thus, we intentionally don't discuss convtroversial, ineffective, or under-studied procedures here. The following document includes descriptions of various surgical procedures, highlighting the purposes of each, along with potential outcomes and consequences.

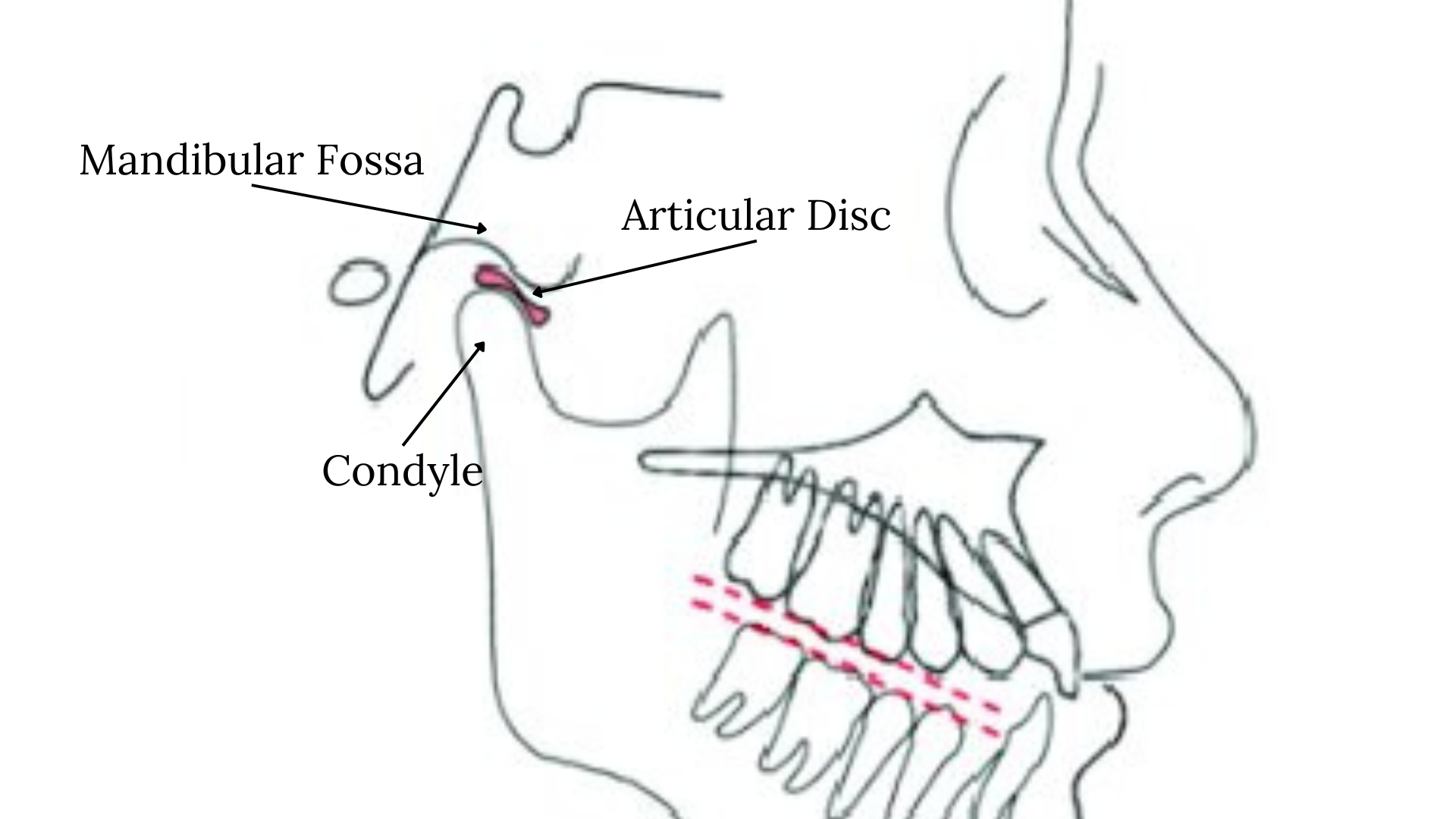

Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ)- The complex joint connecting your mandible to your skull and allowing for translation

Mandible- the lower jawbone used for mastication (chewing)

Maxilla- the upper jawbone

Articular Eminence- The anterior extension of the temporal bone (upper TMJ bone) that works as the front-most barrier for the TMJ

Condyle- the posterior-superior portion of the mandible, which extrudes upwards and sits in the glenoid fossa ("socket")

Glenoid Fossa "Fossa"- the "socket" of the joint in which the condyle sits and glides in

Disc/Meniscus- the circular structure between the condyle and fossa that cushions the TMJ and allows for smooth opening and closing of the jaw

Retrodiscal tissue- the vascularized connective tissue positioned behind the disc that plays a key role in maintaining disc stability

Surgery is a procedure to remove, repair, or adjust bodily tissues. Surgery is generally opted for when minimalistic treatment plans do not achieve the intended outcomes, *and* TMD is severely negatively affecting the patient's life. In some cases, (such as with condylar fractures or ankylosis) surgical intervention may be necessary to prevent structural degeneration, though the occurrence of these is exceedingly rare. Just like with any other specialty, there are risks involved with surgical procedures. It is recommended to fully understand the potential outcomes of surgical procedures before making commitments. Success rates are often benchmarked by reduced pain levels and/or improved mobility, unless there is a more specific goal of the procedure. We like to avoid using success rate as a determining factor of whether or not procedures are "effective" as the parameters for success widely vary by study and case.

Arthrocentesis

Arthrocentesis is lavage of the TMJ space, often using two needles and a saline isotopic solution to flush out inflammatory mediators, clear adhesions, and improve joint mobility. It is by far the least invasive procedure, not involving any incisions. It is often done along with an arthroscopy, though can also be done on its own with the patient under local or general anesthesia. There is very little risk of complications with this procedure.

Arthroscopy

An arthroscopy is a minimally invasive procedure, frequently used as a diagnostic or therapeutic measure for internal derangement and other diseases, in which one or more very small incisions are made to view the superior joint cavity and perform various operations. Arthroscopic procedures may vary based on the patient's needs and the surgeon's preferences. In the past, many surgeons adhered to the McCain arthroscopic "levels" classifications, though arthroscopic procedures do not escalate lineraly as this implies, and often vary in technique by surgeon, institution, or country.

An initial arthroscopy would typically involve a single incision followed by a series of simple procedures including joint lavage (arthrocentesis), lysis of adhesions, and corticosteroid injections. For simplicity we'll refer to this most basic arthroscopic technique as simply an "arthroscopy." This is typically an outpatient procedure. Masticatory function (chewing) should mostly return to its pre-operative state within a few weeks. Some surgeons and institutions practice more aggressive arthroscopic techniques, involving one or more incisions to perform limited types of diskopexy (disc repositioning) or to implant autogenous grafts (fat, muscle, fascia), though performing such procedures arthroscopically is highly controversial.

The success rate of arthroscopies is often cited around 80-90%, though success varies by technique. Complications include but are not limited to, nerve damage, hemmorhage, hemarthrosis, and damage to the articular fibrocartilage. Serious complications occur in fewer than 1% of arthroscopies. Hemarthrosis is nearly inevitable with any surgery operating on the TMJs.

Arthroplasty

Arthroplasties are open surgeries used to reconstruct or recontour the TMJs and simultaneously perform various procedures. They are often used to address unresolving or degenerated internal derangement. Being open procedures, arthroplasties have a broader scope of possible interventions than arthroscopies, at the cost of being notably more invasive. With open procedures, scar tissue will form inside the joint, making future procedures more difficult, increasing the risk of complications. Some operations that constitute arthroplasties include disc repositioning (plication, discopexy; sutures, bone anchors), discectomy (removal of the disc), disc replacement (autogenous grafts: fat, muscle, fascia), and condyloplasty among others. The following procedures, which are most typically performed in open surgeries (arthroplasty), are the most commonly used to address internal derangement.

Diskopexy

Diskopexy is a procedure to reposition the disc. The procedure's name is a broader term with the epithet literally meaning "disc fixating." A discopexy typically involves the surgeon initially lysing adhesions to free the disc. The disc is then sutured to the condyle and lateral capsular attachment. The disc may be recontoured if misshapen. Alternatively, in cases with advanced internal derangement (Wilkes stage III and IV), the surgeon may opt for using the glenoid fossa as the anchor point instead. An eminoplasty using a diamond bur may be performed if the articular eminence prevents proper translation.

An alternative form of diskopexy uses bone anchors to secure the disc. In this procedure, Mitek anchors and sutures are used for disc stabilization on top of the condyle. The clear benefit of this technique over a standard plication is that it would reduce the dependence on soft tissue structures holding up following the procedure, reducing recurrence rates. Surgeons have reported some issues with this procedure, including post-operative crepitus and severe adhesions in the superior joint space. However, based on studies and clinical trials, it is possibly the most effective disc repositioning technique and utilized widely by maxillofacial surgeons.

Disc Plication

Disc plication is a procedure to reposition the disc. Disc plication is a specific technique under the broader term of diskopexy. The retrodiscal tissues are the elastic and vascularized connective tissues located behind the disc. When the disc is displaced anteriorly or anteriorly deviated (medially or laterally), the retrodiscal tissues stretch, holding the disc in the anteriorly displaced position. A disc plication procedure involves removing a wedge of retrodiscal tissue and then suturing the remaining tissue to the posterior ligament. This shortens the stretched posterior attachment and allows the disc to be repositioned back on top of the condyle. The surgeon may also perform an anterior release on the anterior connective tissue and/or an eminoplasty (reshaping of the articular emininece) to improve disc mobility. These decisions are made depending on how the TMJ appears to function immediately following the main procedure.

Discectomy

Discectomy is a procedure to remove the disc. This procedure is opted for if the disc is severely damaged, specifically if it is perforated or malformed beyond repairability. Discectomy is typically only used for late stage internal derangement. The procedure primarily involves removing the damaged portion of the disc (usually the central avascular portion, and sometimes parts of the attachments). The posterior and anterior attachments are not entirely resected as to prevent excessive fibrosis following the procedure. Studies and clinical trials show that discectomy without replacement has a high success rate, with patients' symptoms improving following the procedure, most notably pain and range of motion. Benificial adaptive changes in the TMJ occur frequently following discectomy.

An approach to discectomy involves inserting a temporary interpositional silicone implant. This promotes the creation of fibrous tissue lining and acts as a temporary spacer between the condyle and glenoid fossa, preventing immediate bone on bone contact.

Another approach involves replacing the disc with autogenous grafts. The autogenous grafts are usually composed of dermis, auricular cartilage, fascia, and muscle. Studies reveal that discectomy with replacement may be no more effective than discectomy without replacement at improving symptoms.

Condylotomy

Modified condylotomies are osteotomy procedures that reposition the posterior section of the mandible (condyle and part of the ramus) inferiorly (downward) and anteriorly (forward) to increase the joint space. The goal of this procedure is to increase the joint space to lighten the load on retrodiscal tissues. It also may have a goal of reducing the disc. Disc reduction is an unlikely outcome of this surgery for later-stage internal derangement, and is very unlikely to be recommended to a patient suffering with prolonged disc displacement.

This procedure comes with notable complications and risks. Maxillomandibular fixation ("clamping the jaw shut") is done during recovery to attempt to prevent occlusal changes. For at least a few weeks following the procedure, a nonchewing diet is necessary. A common complication of this surgery is that it can result in an anterior open bite, or worsen a pre-existing open bite, which is why this procedure is advised against for patients with a pre-existing anterior open bite or class II malocclusion. Because of all the described factors, it's exceedingly unlikely that surgeons will recommend a modified condylotomy to treat standard internal derangement, though there are other edge-case TMD that could benefit from the modified condylotomy.

Joint replacement is a procedure to replace part of or the entire TMJ structure (condyle-fossa unit) with an autogenous or alloplastic graft. Due to the highly invasive and consequential nature of this procedure, it is only used for patients with end-stage TMD: severe degenerative joint disease, condylar fracture, recurrent ankylosis, a pre-existing prosthesis that needs replacement, and some other extreme cases. Because of the results and complications that come along with autogenous TMJ grafts, they have mostly been ruled out of use in modern surgical practices. Thus, alloplastic protheses are the go-to for joint replacement surgeries. Alloplastic prostheses come in stock or custom forms, both with their own benefits. Custom replacements are often necessitated when there are severe deformities or incompatibilities between the stock joint and patient's anatomy. There are a handful of other specific cases that would warrant a custom replacement over stock. This decision should be made by the surgeon and patient.

Prior to the procedure, CT scans are taken to plan the procedure through a wax or virtual model. An initial alloplastic joint replacement procedure would typically involve two incisions, pre-auricular (in front of the ear) and sub-mandibular (under the mandible; ramus). A condylectomy (removal of the condyle) would be performed and the fossa and condyle prostheses will be screwed into place. In addition to the joint replacement, maxillary osteotomies (often referred to as orthognathic surgery or Le Fort osteotomy) are often performed along with a custom replacement to align the maxilla with the mandible to fix occlusion. Note that depending on the specific case, various other procedures can be performed, such as bony resection for ankylosis and tumor resection, among others.

Modern prostheses used for total joint replacement are significantly more effective than the ones of the past. The majority of modern replacements are successful, with success defined as improvement in pain and mobility. Complications can range from mild to serious, with the most prevalent being infection and nerve damage. Alloplastic joint replacements come with other obvious consequences, such as a limited range of motion (especially laterally).

For obvious reasons, only the most prevalent and utilized procedures are detailed on this page. Other procedures to address temporomandibular disease certainly exist. Some surgeons may perform variances of standard procedures, based on their background and preferences. For rarer, more extreme forms of TMD requiring surgical intervention, such as skeletal trauma, it is highly recommended to use other sources as guidance.

Orthognathic surgery is a procedure to realign the occlusion, involving osteotomies of the maxilla and/or mandible. It is frequently used for TMD, as occlusion is dependent on mandibular positioning, which can change due to remodeling/ankylosis of the TMJ structures. As mentioned in the last section, maxillary osteotomies are the most commonly used orthognathic procedures for TMD, frequently performed alongside a joint reconstruction. It is also common for surgeons to perform orthognathic surgery (mandibular, maxillary, or bimaxillary) outside of joint replacement surgeries to correct malocclusion.